Bush’s Blunder

President George W. Bush told the nation and the world about the commencement of Operation Iraqi Freedom at 10:16 p.m. ET on March 19, 2003. As he spoke, American forces were already on the attack eight time zones away.

Bush said that the invasion was about “helping Iraqis achieve a united, stable, and free country.” And, he added, the mission “will require our sustained commitment.”

The Iraqis, of course, had not asked for that “help,” and a “sustained commitment” to a country 6,000 miles away was not what Americans wanted, but it was exactly what Bush and his neoconservative advisers wanted. Some had dreams of re-colonizing the Middle East; others had dreams of securing its oil.

For his part, Bush dreamed even further; he later said his real goal was “ending tyranny in our world,” with the war in Iraq as just a stepping stone. Nobody ever said that the neocons were realistic.

It had been clear that Bush wanted a war on Iraq since his January 29, 2002, “Axis of Evil” speech. This author wrote immediately that such a war would be a bad idea. Anticipating “regime change” (a nice way of saying “conquer someone else’s country”), I wrote that we would be going into a place that we didn’t know, egged on by false friends, such as the notorious double-dealer Ahmed Chalabi, who was as popular in Washington, DC, think-tanks as he was unpopular on the streets of Baghdad. I wrote at the time:

Is this what we can expect in Iraq — our chosen friends displaced by our unchosen enemies? There’s no way to know. But as the American experience in Afghanistan suggests, we don’t know much of anything about Muslim politics. Indeed, about the only thing we can know for sure about Iraq is this: American gains will be secure for only as long as Americans remain.

So, of course, the war proved to be a fiasco. As one history-minded observer wrote last week: “This month marks the 20th anniversary of the greatest western foreign policy disaster since the Fourth Crusade. It was the pre-eminent modern-day example of folly, driven by wishful thinking, utopianism and a lack of interest in history and how human societies differ.”

From left to right: Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, President George W. Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld during a meeting on August 14, 2006, at the Pentagon. (TIM SLOAN/AFP via Getty Images)

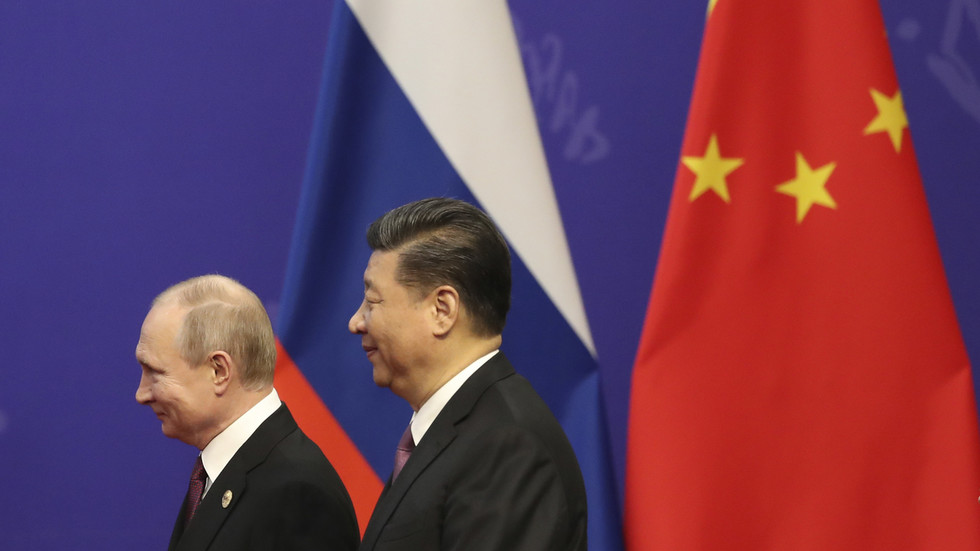

To be sure, historians will be evaluating Iraq and all its global implications for a long time to come. But it’s already clear that the war pushed Iran, Russia, and China into a tighter alliance, which they considered to be self defense. So, how should the U.S. deal with a hostile Eurasian bloc in the heart of the “world island”? That’s a riddle that will preoccupy foreign policymakers for the next hundred years or more.

But for now, we might just consider some of the domestic effects of Bush’s war.

We can start with the outright costs of the war. Then we can observe various political costs — specifically, how the war broke the Bush political dynasty. More broadly, the war broke our faith in government experts. It also clarified the reality of the so-called “Uniparty,” which helped in the rise of Donald Trump in 2016. And finally, the war validated the thinking behind America First.

Let’s look at each of these effects in turn.

Cost of the War

Brown University’s Watson Institute estimates that between 276,000 to 308,000 people died in the second Iraq War, including 4,572 American troops, 3,588 U.S. contractors, and as many as 207,156 Iraqi civilians. Wounds and injuries — immediate and slow-acting — account for tens of thousands more. The full scope of the human tragedy, particularly for the people of Iraq and the region, can never fully be grasped.

A visit to Section 60 at Arlington National Cemetery, resting place of many heroes from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, is sobering, especially as one notices that the interment services keep coming.

Connect with us on our socials: