NAFEM Window and BDC (USD, GBP, CAD, EURO & YUAN) Rates – April 9, 2025

Closing Rate- N1,611.55

Read More

Comment

0

I didn’t embrace Islam and Yoruba culture for Tinubu — Reno fires back at Obi’s aide

So, Mr. SA Media to Peter Obi, please note that while your boss was chasing money up and down as a typical trader, I was chasing God.

Read More

Comment

0

Petrol price likely to fall as FG pushes crude-for-naira deal

We are ensuring that the crude-for-naira initiative helps stabilise the naira...

Read More

Comment

0

CBN posts $6.83bn balance of payments surplus for 2024

The balance of payments position recorded a significant improvement...

Read More

Comment

0

Joe Rogan, Dave Portnoy and Ben Shapiro are among Trump backers now questioning tariffs

Rogan called the idea “crazy.”

Read More

Comment

0

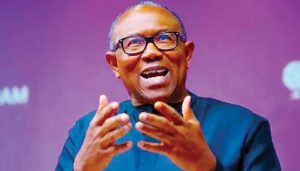

Obi warns: Nigeria on the verge of collapse

We are sliding backwards, and we must retrace our steps to save the country.

Read More

Comment

0

FG doubles down on Crude-for-Naira deal

Key stakeholders, including representatives from the Central Bank of Nigeria and NNPC, participated in the meeting, where they discussed progress and addressed challenges. The government remains focused on leveraging strategic fiscal measures to...

Read More

Comment

0

The world will shake to its core: What a US strike on Iran could unleash

In this complex and explosive environment, the international community is also paying close attention to Russia, which, according to Bloomberg, has expressed its willingness to act as a mediator in the dialogue between the US and Iran.

Read More

Comment

0

Kemi Olunloyo rejects condolences, distances self from late father

“My father destroyed our family unit... He tortured us emotionally and physically.”

Read More

Comment

0

TikTok’s algorithm can’t leave without China’s permission, delaying sale to US

U.S. lawmakers remain skeptical, concerned ByteDance may retain influence even after a sale, posing a national security threat.

Read More

Comment

0