[ad_1]

South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, whose rise in the polls has reshaped the campaigns in Iowa and New Hampshire, found himself at the center of the sharpest attacks. Former vice president Joe Biden, who has remained at the top of national polls through the year, also became an occasional target.

That Buttigieg wore the biggest bull’s eye was not unexpected. His rise this fall has threatened the candidacies of many of his rivals, but perhaps none more so than Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.).

Buttigieg’s surge in Iowa and New Hampshire has come at the expense of Warren, whose candidacy has slid as his has risen. Both appeal in part to the same kind of voters — well-educated whites. But Buttigieg’s rise also has no doubt contributed to blocking the breakthrough that Klobuchar believes will come but has not materialized.

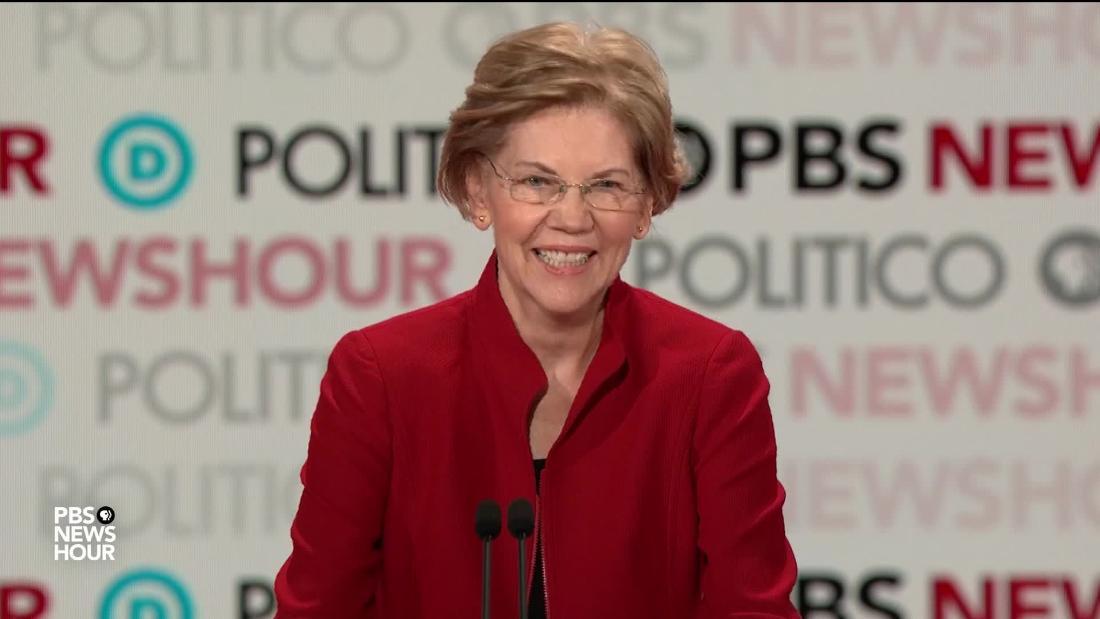

Warren led off the attack on Buttigieg, criticizing candidates who take contributions from wealthy individuals at high-dollar fundraisers, a policy she has eschewed as a presidential candidate.

Others in the field do this, including Biden, but Buttigieg chose to respond. “This is our only chance to defeat Donald Trump,” he said. “And we shouldn’t try to do it with one hand tied behind our back. The way we’re going to win is to bring everybody to our side in this fight.”

Warren hit back harder. “The mayor,” she replied, “just recently had a fundraiser that was held in a wine cave full of crystals and served $900-a-bottle wine. . . . Billionaires in wine caves should not pick the next president of the United States.”

Buttigieg countered again. “This is the problem with issuing purity tests you cannot yourself pass,” he said.

When Warren then said, “I do not sell access to my time,” Buttigieg fired back, noting that she had raised money in her Senate campaigns with the same kind of high-dollar fundraisers she was now criticizing. “Your presidential campaign right now as we speak is funded in part by money you transferred, having raised it at those exact same big-ticket fundraisers you now denounce,” he said.

In the moment, on the stage, it seemed advantage Buttigieg. Whether he sustains that between now and when the voters begin to cast their ballots is another question. He is likely to face continued criticism and scrutiny.

As Warren and Buttigieg were squabbling, Klobuchar broke in to admonish both for their exchanges. “I did not come here to listen to this argument,” she said. “I came here to make a case for progress.”

Minutes later, however, she launched into her own criticism of Buttigieg, accusing him of what she said was his previous mocking of the collective experience of many of his older and more experienced rivals.

Klobuchar’s disdain for the Indiana mayor had surfaced before. In last month’s Atlanta debate, she hesitated until the very end of the evening to challenge his youth, relative inexperience and male privilege, as she had done publicly along the campaign trail.

Her exchange with Buttigieg was less focused but no less pointed than the clash between Buttigieg and Warren. It also was less conclusive. What it revealed was the apparent visceral dislike of both candidates for each other.

Overall, Klobuchar delivered the kind of performance she wanted, one that emphasized her focus on middle-ground policies, Midwestern values, humor and a desire to produce results in office.

Biden drew criticism, as he has before, for his vote to authorize the Iraq War and for his opposition to Medicare-for-all, a central plank in the candidacy of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.). Biden parried on health care and chose to let the Iraq issue slide by.

More notable, perhaps, was his overall performance, which included some of the strongest moments he has had in any of the six candidate forums. Biden was crisp in defending himself against criticism that he is naive to believe he can gain cooperation of Republicans if he becomes president.

“I refuse to accept the notion, as some on this stage do, that we can never, never get to a place where we have cooperation again,” he said. “If that’s the case, we’re dead as a country. We need to be able to reach a consensus. And if anyone has reason to be angry with the Republicans and not want to cooperate, it’s me, the way they’ve attacked me, my son and my family.”

He was referring to attacks from Trump and Republicans over his son Hunter’s position on the board of an energy company in Ukraine while Biden was vice president and calls by some in the GOP for them both to be called to testify in the impeachment hearings or face a congressional investigation.

He showed humor when he was asked whether he could commit to running for a second term, at age 82, if he wins the presidency in 2020. “No, I’m not willing to commit one way or another. Here’s the deal. I’m not even elected one term yet, and let’s see where we are. Let’s see what happens. But it’s a nice thought.”

When the topic of Afghanistan was raised, and the revelations published in The Washington Post about how leaders had misled the public about progress in the war, Biden answered by explaining that he, almost alone among senior officials in the Obama administration, had opposed the troop surge.

This was the first debate with fewer than 10 candidates on the stage. Whether it was the experience of six months of debates or the smaller number of candidates, the debate produced moments helpful to virtually everyone.

Sanders showed his appetite for challenging the economic system. Entrepreneur Andrew Yang, as in past debates, talked about the challenges of an economy in transition and spoke in language fresher than some of his more experienced rivals. Businessman Tom Steyer showed his commitment to the threat of climate change. Warren showed her passion for attacking corruption.

Thursday’s debate, hosted by PBS and Politico and held at Loyola Marymount University, was the sixth of the year for the Democrats. But it delivered no definitive answers to the overriding question for most Democrats, which is who can beat Trump. Biden emerged in a solid position. Buttigieg weathered the first serious attacks. Warren showed determination to mount a comeback. Klobuchar let others know she intends to be a factor in Iowa. Sanders showed he should not be taken for granted.

Thursday marked the final tuneup before election year arrives. The next time the Democrats debate, the stakes will be much higher. That forum will take place in mid-January in Iowa, a few weeks ahead of the caucuses that start the nominating process. By the end of February there will be three more debates and three more contests.

Democratic voters have shown a reluctance to make firm commitments to one or another of the candidates, but decision time is approaching quickly. Those first contests could winnow the field to a relatively few candidates — or signal a long war and the possible emergence of someone who wasn’t on the stage in Los Angeles, namely Mike Bloomberg, the billionaire former mayor of New York.

The last debate of 2019 offered a preview of what comes next as each of the Democratic candidates tries to convince their voters they are singularly equipped to lead the party to victory against Trump.

[ad_2]

Source link

Connect with us on our socials: