Researcher uncovers alternative treatments for prostate cancer

The findings suggest that these alternative treatments may offer better outcomes with fewer side effects.

Read More

Comment

0

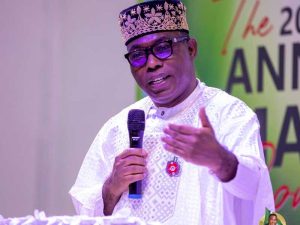

Adebayo accuses Tinubu’s government of lawlessness

“The government is operating outside the bounds of the law,” Adebayo said during a press statement.

Read More

Comment

0

Senators push for probe into possible insider trading following Trump’s tariff adjustments

The request follows claims that stock market movements may have been influenced by early knowledge of the tariff adjustments.

Read More

Comment

0

China opens door to talks, but rejects blackmail after Trump’s 125% tariffs

"Pressure and blackmail will not work," said a Chinese government spokesperson.

Read More

Comment

0

Nigeria lost nearly 15,000 nurses, midwives to UK in five years – Report

The migration has contributed to a growing shortage of healthcare workers in Nigeria, particularly in the public health sector.

Read More

Comment

0

NBC bars Eedris Abdulkareem’s ‘Tell Your Papa’ from airplay on radio, TV

Abdulkareem has defended the track, describing it as a reflection of societal frustrations.

Read More

Comment

0

Moises Caicedo’s £160k Audi impounded by police for driving without valid license

Caicedo’s car was impounded and he was fined for the violation.

Read More

Comment

0

Yuan plunges to lowest level since 2007 amid ongoing US-China trade war

“The yuan's drop reflects ongoing concerns about the prolonged trade conflict,” said an economic analyst.

Read More

Comment

0

Champions League humiliation highlights Real Madrid’s squad depth crisis

Extract:

Real Madrid’s loss to Arsenal has highlighted their lack of depth, with injuries forcing Ancelotti to rely on a limited core of players.

Read More

Comment

0

Nnamdi Kanu’s N50bn suit against FG thrown out by court

“The court lacks the jurisdiction to entertain the matter,” Justice James Omotosho ruled.

Read More

Comment

0